Project Summary

Strategies to Address Adverse Effects of Distiller’s Grains on Prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in Feedlot Cattle

- Principle Investigator(s):

- Jim Drouillard, T. G. Nagaraja, David Renter

- Institution(s):

- Kansas State University

- Completion Date:

- May 2008

Background

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is an important foodborne pathogen that causes hemorrhagic colitis, hemolytic uremic syndrome and thrombocytopenic purpura in humans. The gastrointestinal tract of cattle is the major reservoir of the organism and cattle feces are an important source of infection. Escherichia coli O157:H7 contamination occurs throughout the beef production and processing systems with contamination prevalence of 11 to 28% in cattle feces, 11% on hides, 3 to 28% of carcasses, and up to 0.3% of retail raw ground beef. Despite intense surveillance of meat processors by the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service following the 1994 regulatory declaration of E. coli O157 as an adulterant in raw ground beef, the number of laboratory-confirmed human illnesses caused by E. coli O157 continues at unacceptable levels (1.7 cases per 1,000,000 populations in 2002). Failure to control E. coli O157 will result in continued human illnesses, loss of consumer confidence in beef, costly recalls of beef products, and has the potential to affect beef export markets. Control strategies aimed at reducing the prevalence and concentration of E. coli O157 in cattle feces, thus reducing the overall number of bacteria entering both the food and environmental pathways, constitutes an important approach for reducing the risk of human infections.

The U.S. fuel ethanol industry has grown substantially during the past decade, resulting in large quantities of distillery byproducts that are available as an economical source of feed for cattle. Distiller’s grains commonly contain the protein fraction of the grain, along with the bran, which is high in fiber, and the germ, which is high in oil. Because of the high proportion of fiber in distiller’s grains, they are well suited for use in dairy and beef cattle. In the past two years, the researchers have conducted two studies that show a positive association between feeding of distiller’s grains and fecal prevalence of E. coli O157 in cattle.

The stated objectives for this work were to determine the effects of supplementing dried distiller’s grains with solubles (DDG) on fecal shedding of E. coli O157 in cattle fed steam-flaked corn (SFC) grain diets. Also, the researchers included supplementation of dry-rolled corn (DRC) to determine whether corn grain, processed to increase availability of starch in the hindgut, could be used as a pre-harvest intervention strategy to reduce fecal shedding of E. coli O157:H7.

Methodology

Steers fed their experimental diets for 52 days, after which fecal samples were obtained from each animal via rectal palpation to identify a subset of steers that were not actively shedding wild-type E. coli O157 at the start of the experiment. Thirty-one steers were identified as being negative for carriage of E. coli O157 (7 steers in the treatment consisting of steam-flaked corn with dry-rolled corn, and 8 in all other treatment groups).

Fecal Sampling and Detection or Enumeration of NalR E coli O157

Fecal samples were collected from each animal before inoculation (day 0) to determine the prevalence of wild-type E. coli O157. After oral challenge with NalR E. coli O157 (day 0), fecal samples were collected from steers three times each week (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday). At the termination of the study all calves were euthanized and submitted for post-mortem examination. Animal were euthanized in groups on three consecutive days, with equal numbers of animals from each treatment represented each day. Contents from the rumen, cecum, colon, and rectum were collected and the concentrations of NalR E. coli O157 were determined as described above.

FINDINGS

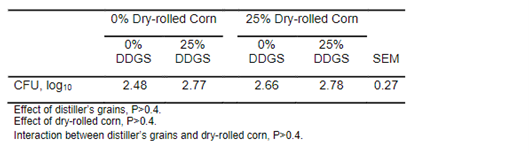

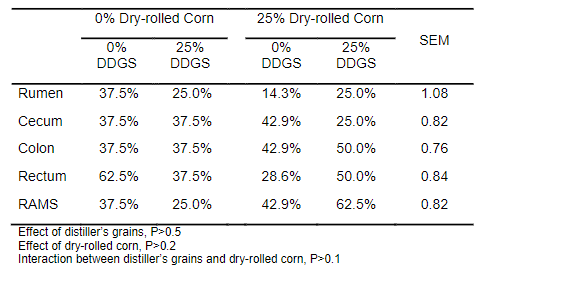

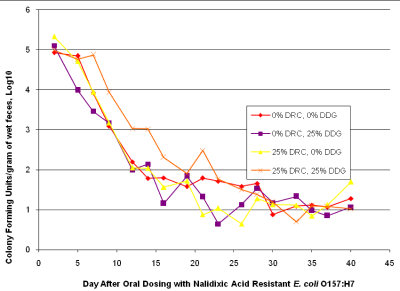

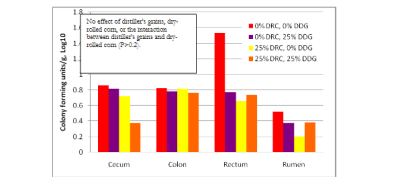

Concentrations of NalR E. coli O157 in feces are shown in Figure 1. Concentrations on day 2 after inoculation were approximately 1 x 105 CFU/g of feces for all treatments. Shedding rates gradually declined for all treatments, falling to between 1 and 2 log CFU/g by day 40 after inoculation. There were no discernible differences in shedding rates for cattle fed diets with 0 and 25% dried distiller’s grains or 0 and 25% dry-rolled corn. This observation is in direct opposition to the stated hypothesis. It was speculated, on the basis of previous studies, that adding dry-rolled corn to finishing diets would increase starch supply to the hindgut where it would in turn be fermented, thus creating an environment less suitable for colonization by E. coli O157. Based on the results of this study, adding dry-rolled corn to finishing diets is not an effective intervention for reducing concentrations of E. coli O157:H7. A separate statistical analysis that was limited only to those samples that contained detectable levels of NalR E. coli O157 was conducted (Table 2). This analysis also revealed no significant effects of adding dried distiller’s grains with soluble or dry-rolled corn. The researchers of this study recently completed a companion experiment to assess prevalence of wild-type E. coli O157 in cattle fed diets identical to the diets used in this study. In that study, prevalence of E. coli O157 was numerically higher (but not significant) in cattle fed distiller’s grains compared to cattle fed diets without. As in the present study, dry-rolled corn did not impact prevalence rates. Concentrations of NalR E. coli O157 in various locations of the gastrointestinal tract are shown in Figure 2, and prevalence’s are shown in Table 3. Diet did not influence shedding rates or the proportion of digesta samples from the rumen, cecum, colon, or rectum that tested positive for NalR E. coli O157. These results are in contrast to previous findings with experimentally inoculated cattle, which revealed much higher concentrations of NalR E. coli O157 in cattle fed distiller’s grains compared to cattle fed diets without (P < 0.05). In conclusion, there were no significant differences in dietary treatments that influenced shedding rates of E. coli O157. Addition of dry-rolled corn to flaked corn diets with distiller’s grains was not effective as a preharvest intervention strategy to reduce shedding of E. coli O157 in experimentally inoculated feedlot cattle.

IMPLICATIONS

Feeding distiller’s grains had no impact on shedding of E. coli when added to diets with 0 or 25% dry-rolled corn. When these results are considered in the context of previous experiments, it is apparent that changes in prevalence of E. coli cannot be attributed solely to the use of distiller’s grains. It is likely that other dietary factors may interact with distiller’s grains to create conditions that promote colonization by E. coli O157:H7.

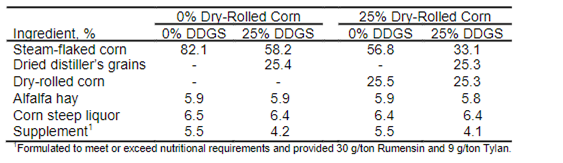

Table 1. Composition of finishing diets (dry basis) containing steam-flaked corn (SFC) with or without dried corn distiller’s grains (DDGS) and dry-rolled corn (DRC).

Table 2. Concentrations of NalR E. coli O157:H7 in culture positive fecal samples from steers fed finishing diets with 0 or 25% dried distiller’s grains and 0 or 25% dry-rolled corn following oral dosing with 3.2 x 109 colony-forming units of a 5-strain mixture of nalidixic acid resistant E. coli O157:H7.

Table 3. Probability of NalR E. coli O157:H7 positive samples in various locations of the GI tract at necropsy.

Figure 1. Concentrations of nalidixic acid resistant E. coli O157:H7 in feces of steers fed diets with 0 or 25% dried distiller’s grains (DDG) and 0 or 25% dry-rolled corn following oral dosing with 3.2 x 109 colony-forming units of a 5-strain mixture of nalidixic acid resistant E. coli O157:H7.

Figure 2. Concentrations at necropsy of NalR E. coli O157:H7 in gastrointestinal tract contents from steers fed diets with 0 or 25% dried distiller’s grains (DDG) and 0 or 25% dry-rolled corn (DRC) approximately 40 days after oral dosing with 3.2 x 109 colony-forming units of a 5-strain mixture of nalidixic acid resistant E. coli O157:H7.